Intel SGX and MIT's Sanctum

22 Oct 2024Future tags – TEE Reading SGX Sanctum

Reading Material / Sources:

- MIT CSAIL Secure Processors Part 1

- MIT CSAIL Secure Processors Part 2

- SGX Overview

- Ascend Processor Just a funny aside, this work is from my advisor Professor Chris Fletcher in 2012. During that time, I was in 3rd grade wrecking multiplication table quizzes lol.

- SGX.fail

- Keystone?

General Terms and Definitions

Secure remote computation problem: Overarching goal is to achieve secure remote computation which is defined as executing software on a remote computer owned and maintained by an untrusted third party with some confidentiality and integrity guarantees. Intel SGX is one of the latest (not anymore we have TDX and others, but at the time of Srini writing the document it was) to try to tackle this problem through trusted hardware.

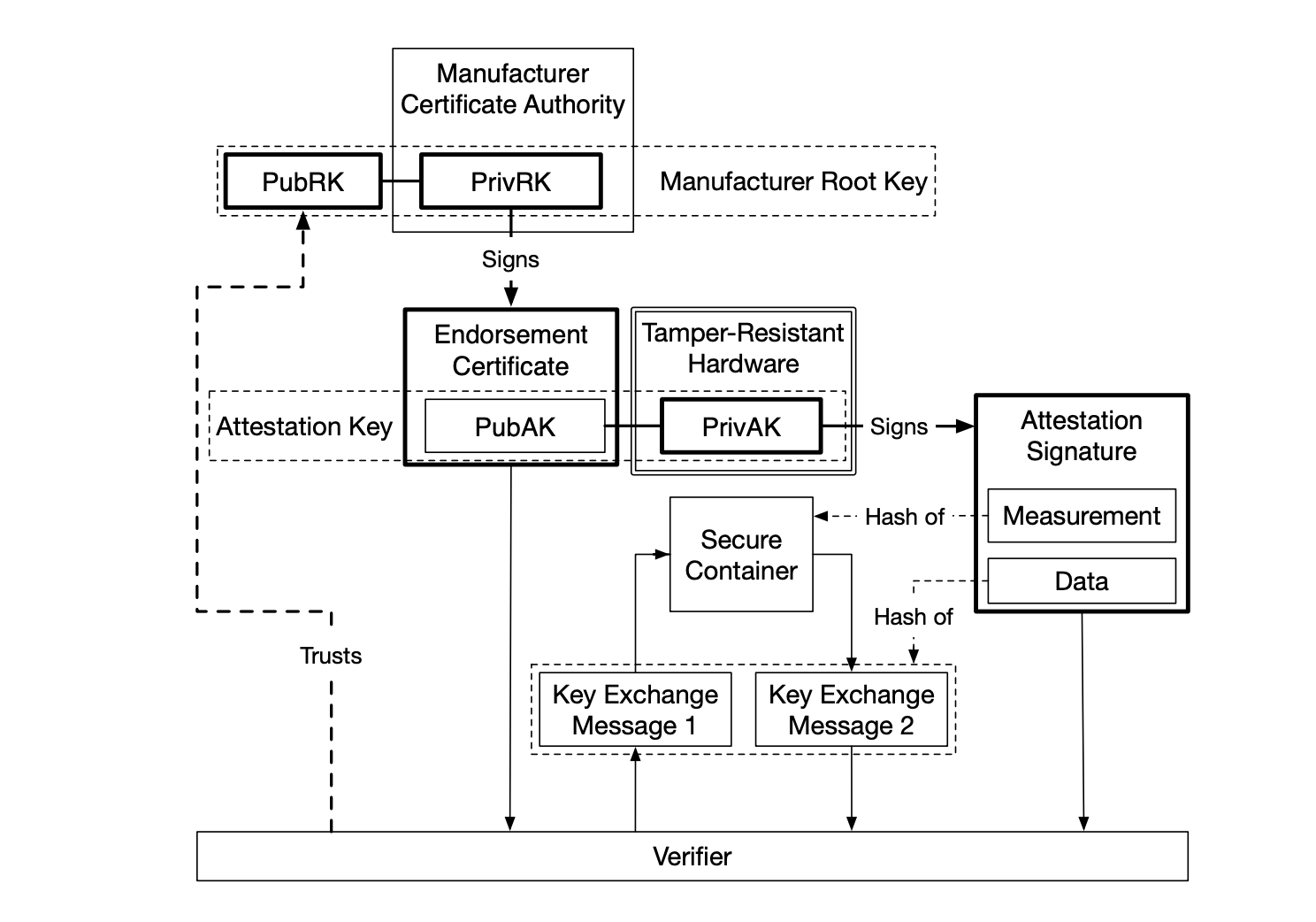

Software attestation: by cryptographically hashing the components of the enclave you can create a trust measurement. Only if this trust measurement matches what the remote party “trusts” does the remote party send over the confidential information. The malicious host can of course put any software they want in the enclave, however, its trust measurement won’t be correct and thus the remote party won’t send over its secret information.

Hardware

Intel Management Engine (ME):

- I remember this was considered ring -3 (SMM is ring -2)

- basically always on and offers Intel complete control over Intel machines (even if they are turned off, the ME is still powered on)

- Responsible for a bunch of hardware resource management and power iirc

Threat model for TEEs

- physical attacks out of scope

- power attacks out of scope

- all privilege level software attacks in scope. Reasoning: SMM code can be compromised (has been demonstrated) therefore it is possible for an attacker to gain access to any exception level.

- software attacks on peripherals

- address translation attacks

- caching timing attacks (I guess this includes broadly all side channel attacks)

General Notes on TEEs

IBM 4765 Secure Coprocessor:

- Has defenses against physical attacks. E.g. sensors to detect tampering. This means it can actually withstand some physical attacks

- Encapsulated an entire computing system within a tamper resitant environment.

- Supports software attestation

Arm TrustZone:

- secure world and normal world

- secure container manages its own page tables

- complete separation is not enforced between worlds. E.g. the caches are not completely separated allowing for cache timing attacks.

- No software attestation capabilities.

Execute-Only Memory (XOM) Architecture:

- Execute sensitive code and data in isolated containers managed by untrusted host software

- Integration of encryption in the processor’s memory controller to block physical DRAM attacks. Vulnerable to replay attacks though. Memory access pattern is not protected as well, opening the door for cache timing attacks.

Trusted Platform Module:

- Relies on auxiliary tamper resitant chip. No modifications needed for the CPU. This is easy to implement but brings weak security guarantees

- TPM relies on software to report its own crytpographic hash. During the boot each stage reports the next stage’s cryptographic hash. This relies on firmware that loads the first stage bootloader to be “correct”.

- Security can be thwarted by an attacker who can re-flash the computer’s firmware

Intel’s Trusted Execution Technology (TXT):

- TPM’s software attestation model + tamper resitant chip.

- Container has exclusive control over the CPU while active

- Signatures cannot be revoked and thus when vulnerabilities were found, Intel had to change TXT’s software attestation model

- Vulnerable to an SMM attacker (the warm resets performed don’t affect the SMM)

Aegis Secure Processor:

- Relies on security kernel inside the OS to isolate containers

- Uses processor features to isolate the secure kernel from the untrusted kernel parts

- Vulnerable to cache timing attacks

- One range is encrypted and another range is HMAC’d. They can overlap. Provides defense against physical DRAM attacks.

Bastion Architecture:

- Trusted hypervisor to provide secure containers to run applications in untrusted operating systems

- Firmware is not trusted. Hypervisor is hashed and sent as part of the trust measurement used in the software attestation

Intel’s Software Guard Extensions (SGX):

- No modifications to the processor’s critical execution path

- Nothing is trusted in the software stack (e.g. firmware, hypervisor, or OS)

- SGX’s TCB includes microcode and a few privileged containers

- Untrusted OS manages the containers page tables. Security is preserved by having the TLB miss hanlder reject translations that don’t belong to the container

- Vulnerable to cache timing attacks

- Provides similar physical attack guarantees to Aegis and Bastion.

Sanctum:

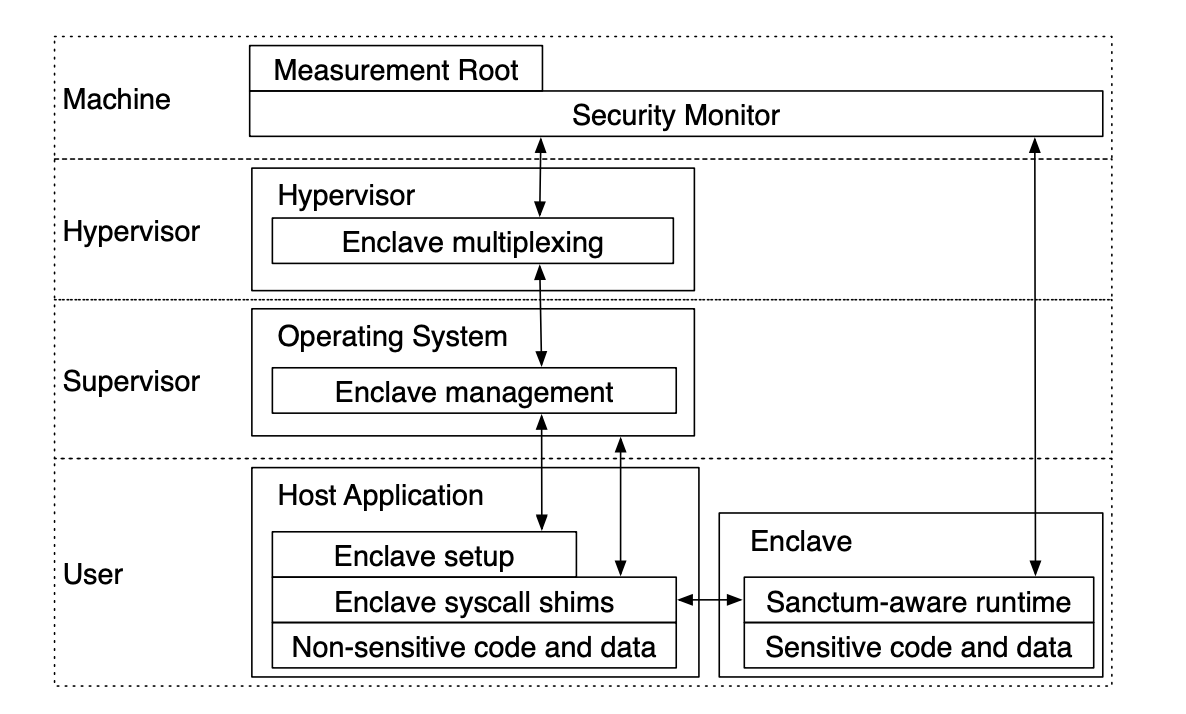

- Relies on a trusted security monitor which is the first piece of firmware executed by the processor. This monitor verifies the OS’s resource allocation decisions.

- Each container maintains its own page table mappings to allocated DRAM regions + handles its own page faults

- No protection from physical attacks. Combined with mechanisms from Aegis or Ascend for physical attack defenses.

Ascend or Phantom:

- Introduce practical implementions of ORAM making the designs resilent to attackers probing the DRAM memory bus (learning secrets through the DRAM access pattern)

- Orthogonal to the other schemes mentioned above

- A combination of Ascend, Sanctum, and Aegis can create a design resilent to software and physical DRAM attacks

Intel SGX

I very much like the statement from the Secure Processors Part 1 text: “While Intel’s Software Guard Extensions fall short of this ideal (as discussed in Part II of this work), the system does present a very attractive programming model: a private process with privacy and integrity guarantees assuming the software of the process itself is not vulnerable.” (this sounds a lot like the declassiflow guarantee, i.e. as long as the software is secure, the system will follow the rules.

SGX Physical Memory Organization

Enclave: The protected environment that contains the sensitive code and data. The enclave is isolated from untrusted software via trust computing and through software attestation. Each enclave is design to protect against malicious software and some physical attacks.

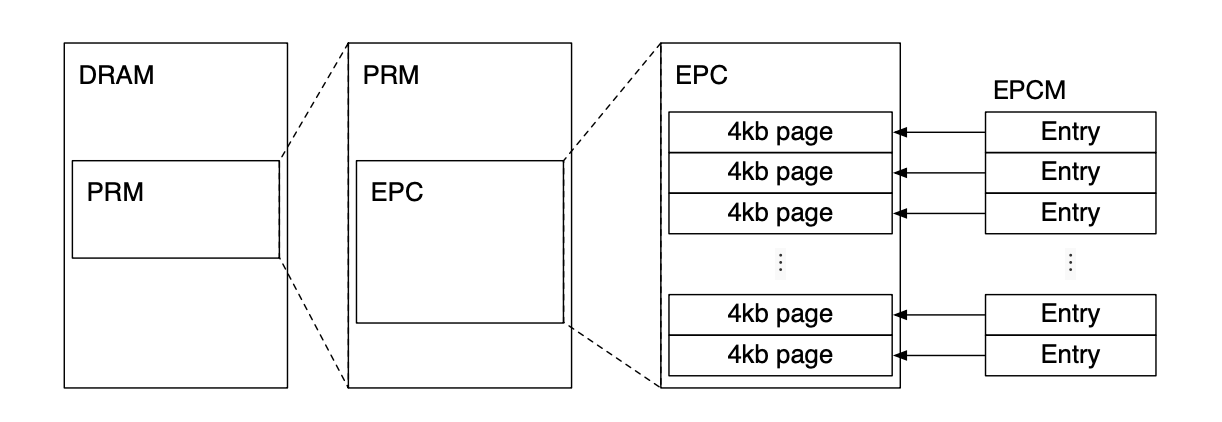

Processor Reserved Memory (PRM): This is a subset of DRAM and can’t be accessed by other software (this includes system software and firmware) and periphals (via DMA).

Enclave Page Cache (EPC): Contents of enclaves and associated data structures are stored here. Subset of PRM. Split into 4 KB pages. This is managed, via special SGX instructions, by system software (hypervisor or OS). Upon allocation of an EPC page, the page is also initialized by (generally) copying from a non-PRM memory page; this is to allow system software to insert the initial code and data to the new EPC pages.

Enclave Page Cache Map (EPCM): System software’s EPC allocation decisions are stored here. One entry per EPC page. Only used for security checks. Contains information about which enclave owns the EPC page to prevent enclaves from interacting with other enclave’s pages.

SGX Enclave Control Structure (SECS): Meta data is stored here. Synonymous to the identity of an enclave. Exclusively used by the SGX implementation. Enclave code is also prevented from acessing SECS and it isn’t mapped in the processors VA space. The trust measurement is also stored here.

SGX Enclave Attributes are stored here which heavily influence the enclave’s execution environment.

SGX Enclave Memory Layout

Enclave Linear Address Range (ELRANGE): The range of an enclave’s virtual address that maps to EPC pages. VA’s outside this range map to non-EPC pages (unprotected).

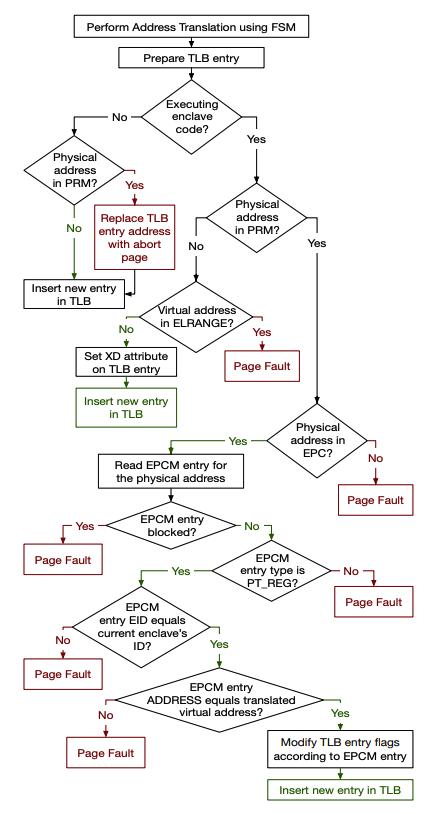

Address Translation Managed by System Software: Since the translation is still managed by system software SGX is open to translation attacks. Per the authors, a lot of SGX complexity is due to the need to mitigate this.

When a EPC page is allocated, the VA is recorded in the EPCM. When the translation is an EPC page the orginal virtual address is checked to match the one recorded in the EPCM entry. The access permissions stored in the EPCM also overwrite the access permissions from the page table entry.

Lastly, VAs in ELRANGE are ensured by the hardware to be mapped to EPC pages.

Thead Control Structure (TCS): Allocated for each logical processor that executes an enclave’s code to support multi-core processors.

State Save Area (SSA): After an exception or interrupt, which require a privilege level switch, the enclave’s context is stored in this structure to prevent exposing its information.

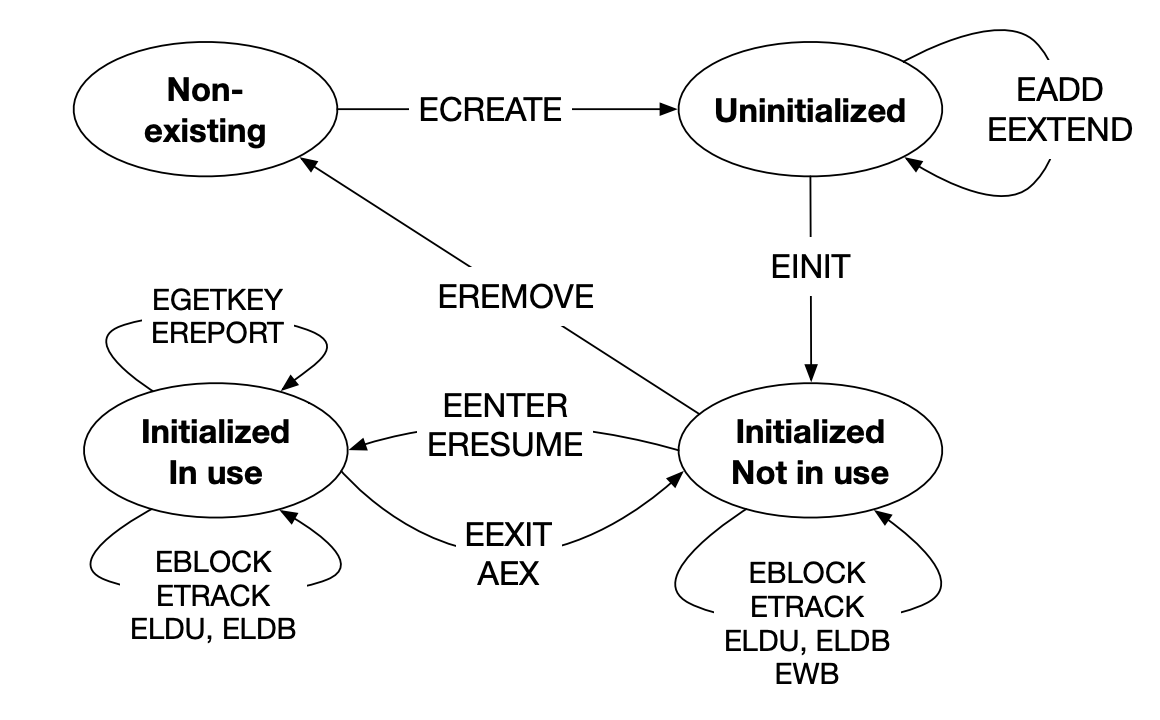

SGX Enclave Life Cycle

Launch Enclave (LE): Used to obtain an EINIT Token Structure that is passed the EINIT instruction to mark an enclave’s SECS as initialized. The LE can be initialized without an EINIT token and is cryptographically signed with an Intel key that is harcoded in the SGX implementation. All code and data must be loaded in to the enclave before the enclave is initialized. This is argued to be unnecessary and should be removed from the SGX implementation

EPC Page Eviction

General Info

- Performed by the system software that does page swapping (OS or hypervisor)

- Symmetric key cryptography is used to protect the confidentiality and integrity of evicted EPC pages. Nonces are stored in Version Arrays (VA)

- TLBs must not contain the address translation of evicted EPC pages

- “One of the least promoted accomplishments of SGX is that it does not add any security checks to the memory execution units (§ 2.9.4, § 2.10). Instead, SGX’s access control checks occur after an address translation (§ 2.5) is performed, right before the translation result is written into the TLBs (§ 2.11.5).”

- Interesting: when paging back in a EPC page, the SGX implementation will clear the least significant 12 bits of CR2 (the 12 LSBs from the faulting address) as they are not necessary for the OS to do its job and make it more difficult for the OS to infer information.

TLBs

- Flushed upon enclave exit

- When an EPC page is evicted, all logical processors that execute that enclave’s code must exit –> wiping the respective TLBs

- This exits are triggered by system software (untrusted), therefore, before the EPCM is marked as free the SGX implementation has to ensure all related TLBs have been flushed.

Failure of SGX

While SGX offers a variety of defenses against software and physical attacks (“direct attacks”), it fails to provide software isolation. E.g. see side channel attacks.

Physical Attacks

Due to lack of information there are not a lot of definitive answers on this front.

- Protected memory (EPC) is protected against DRAM bus tapping attacks (confidentiality, integrity, and freshness)

- DRAM access pattern can be leaked as it is not protected

- Vulnerable to cache timing attacks. No simple modification to provably protect SGX against cache timing side channels

- No mentions about the SMBus which connects the ME to various components on the motherboard

- Defenses aimed at increasing the cost of chip attacks

- Threat model excludes power analysis attacks and other side-channel attacks

Privileged Software Attacks

- Since SGX is implemented in microcode it sits at a higher level than system software.

- SGX regulates all interactions between non-enclave code and enclave code

- Hyperthreading is not disabled! By scheduling an attacker on the same physical core of a victim, the attacker can reveal a lot of secrets like instructions executed or memory access pattern

- Does not protect against passive address translation attacks – leaking the enclave’s memory access pattern

- No mention of uncore PEBS counters. They are vulnerable to side channel attacks via performance counters but the exact damage is unclear

- The enclave’s branch history is vulnerable

MIT’s Sanctum

Same guarantees as Intel SGX but also protects against software attacks that can infer the memory access pattern. Implemented in trusted software (doesn’t use cryptographic keys) which is easier to understand / analyze compared to Intel’s microcode. Sanctum is on the Rocket RISC-V cores which are open sourced and can be analyzed by all researchers. Sanctum adds hardware at interfaces between general building blocks to enforce invariants that uphold Sanctum’s security policy.

Threat Model

All software outside the enclave is considered hostile. The attacker can analyze passively collected data, and mount active attacks such as direct or DMA memory probing, and cache timing attacks. Sanctum does not protect software that leaks its own secrets or “by timing their operations”. I interpret this as Sanctum is not free from all side channels but because of the cache partitioning scheme employed the enclaves are protected from cache side channels. Moreover, Sanctum assumes correct hardware (i.e. doesn’t protect against rowhammer).

I specifically want to poke a hole in one of their assumptions: Sanctum also does not defend against physical attacks and consider software attacks that rely on sensor data to be physical attacks. Specifically, “For example, Sanctum does not address information leakage due to power variations, because software would require a temperature or current sensor to carry out such an attack.” I do not believe this is a valid assumption anymore due to attacks like Hertzbleed that exploit timing variations that are a result of clock frequency which is a result of power consumption. It seems like this is not protected under Sanctum either (there is an indirect assumption that power attacks rely on sensor data).

Sanctum vs. SGX Differences

The only main difference with SGX is that microcode is replaced with the security monitor which runs at the highest privilege level in RISC-V. Additionally, “Sanctum improves upon SGX by isolating cache sets and page tables used to access an enclave’s private memory, as well as microarchitectural state updated as a side effect of enclave execution. The improved isolation defeats attacks that exploit the memory access pattern information leaks that result from cache and page table sharing, as well as attacks attempting to infer private control flow information from observing core state after enclave execution.” Another key difference is that faults are redirected to the enclaves’s fault handler, this removes information leakage from fault timing attacks that SGX is vulnerable to. The key idea behind Sanctum is that software inside the enclave that does its computation and accesses its data inside the enclave is protected from any attack mounted by software outside the enclave. Though I would argue the above is no longer true in the context of Hertzbleed style attacks. There are definitely more implementation differences, but I think I’m currently only interested in the higher level differences between the two.